It’s Alive!

A Swiss public library replaced standard classifications with human curation, collaboration, and a knack for random discovery.

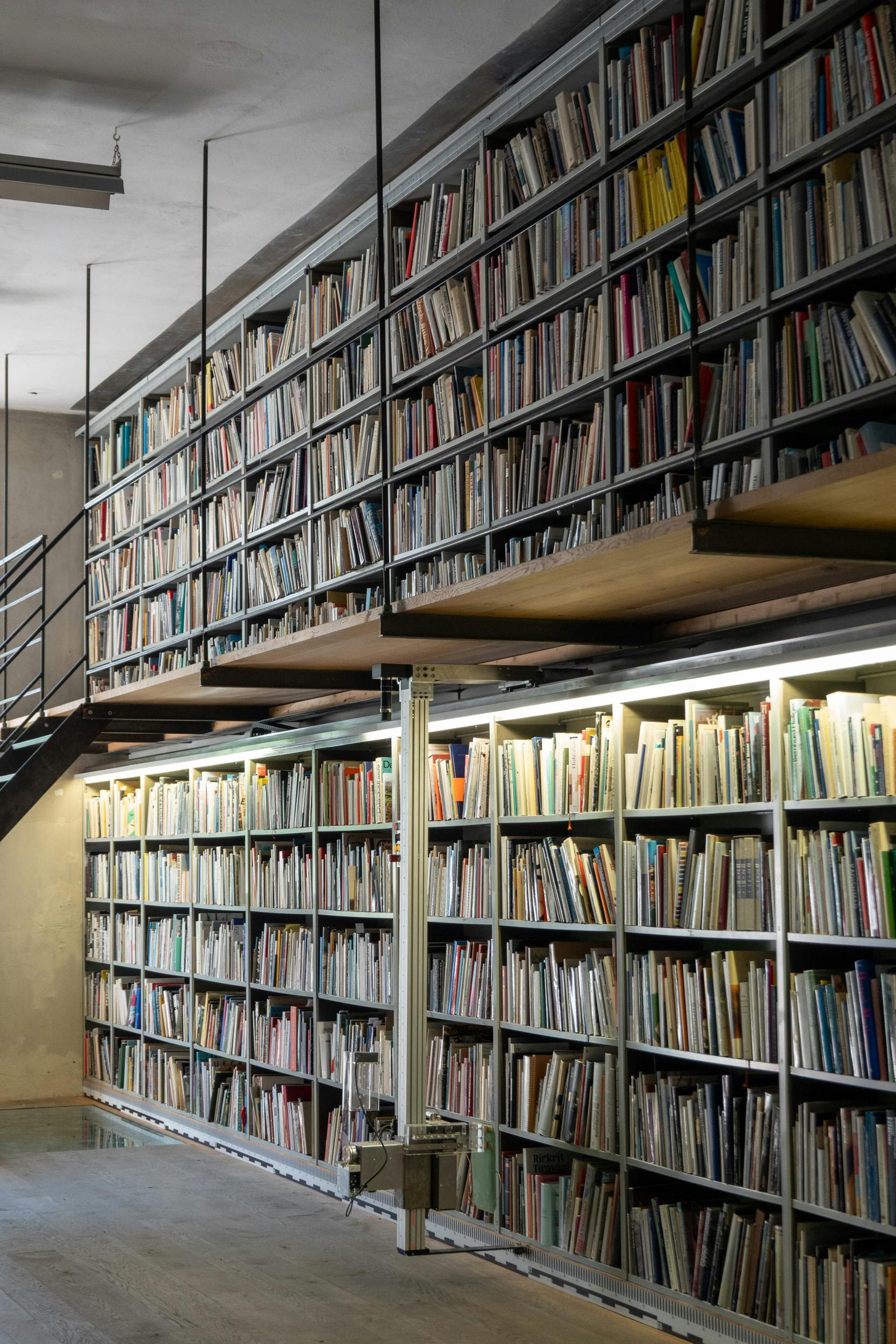

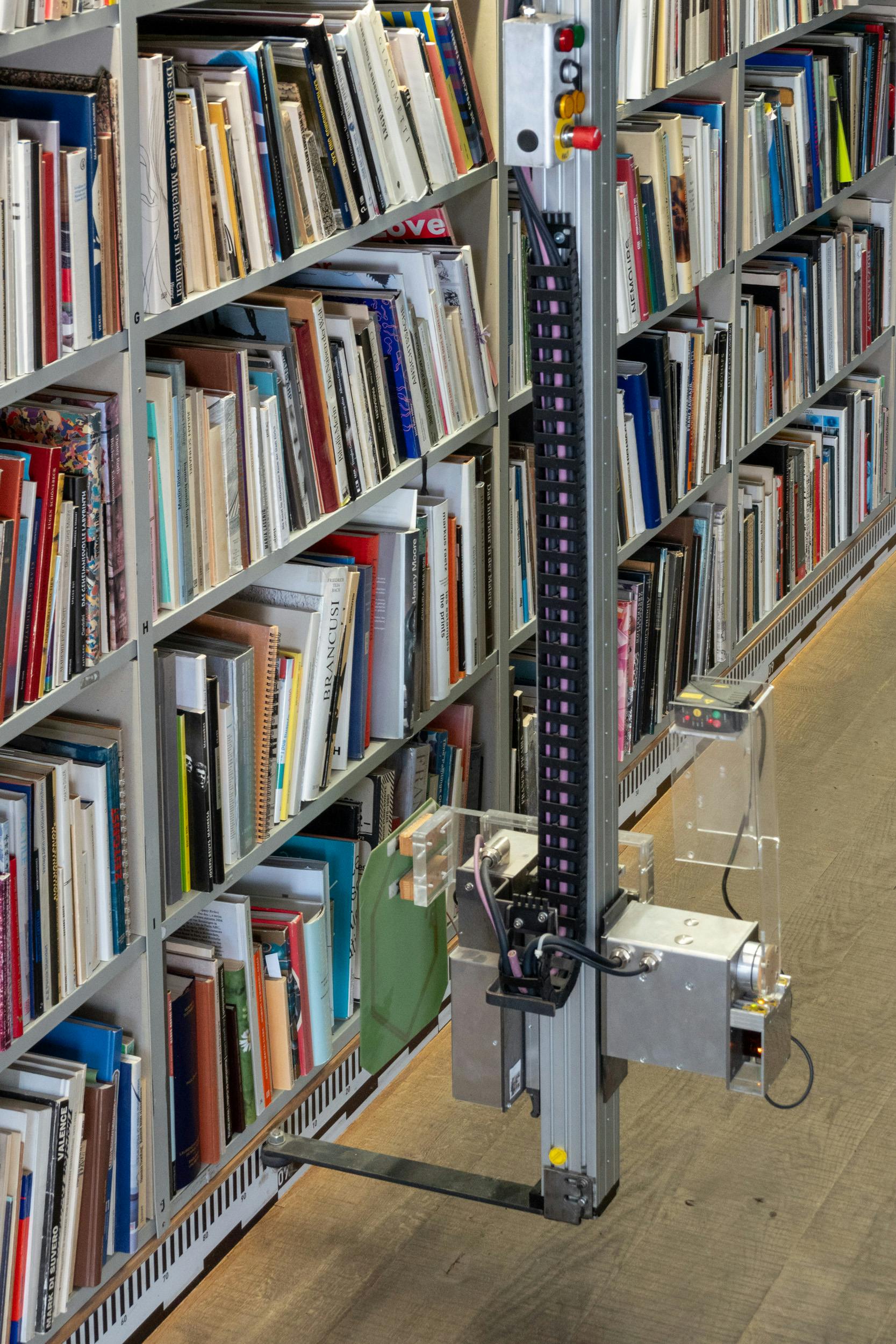

Every night, at 3 AM, a continuous mechanical buzz breaks the library’s quiet stillness. Anchored to the top of the shelving, a robotic, multi-jointed steel arm moves slowly. For two and a half hours, it systematically slides up and down, left and right, scanning all 30,000 books on art, architecture, design, and photography.

Distant and muffled, blending with the natural sounds of the surrounding Alps and the tinkling of a nearby stream, the metallic noise can still be heard outside the building — a former industrial facility in the Sitter Valley, outside St. Gallen, which, until 1990, headquartered the local textile dyeworks.

The former plant now houses one of Europe’s most important art centers, comprising an art foundry — the Kunstgiesserei — a gallery space and museum — the Kesselhaus Josephsohn, honoring the legacy of Swiss sculptor Hans Josephsohn — and the Sitterwerk Foundation. The co-founder and director, Felix Lehner, established the Kunstgiesserei when he was just 22. He left his librarian job after befriending Josephson in the 70s and began producing some of the artist’s impressive bronze castings. Initially headquartered in Beinwil am See, Lehner’s Kunstgiesserei relocated to Sitter in 1994. There, the foundry expanded to include workshops for the processing of wood, polystyrene, coatings, ceramics, and glass. (Metal casting, however, remains its most renowned technique.) The hub’s experimental approach, talent, and keen interest in unconventional materials and production methods won Lehner’s team international fame. For over four decades, the foundry has produced sculptures and installations for some of the most renowned contemporary artists, including Martin Creed, Pierre Hyghe, Beni Bischof, Urs Fischer, George Condo, Katharina Fritsch, and Precious Okoyomon (my favorite) — to mention a few names not bound by NDAs. On June 16, 2025, Lehner will be awarded the most prestigious prize in the Swiss arts, the Prix Meret Oppenheim.

© Marta Dell’Era

Nestled in the Eastern wing of the complex between the workshops and the Sitter River, the foundation’s art library — or Kunstbibliothek — isn’t ordinary at all. The volumes need to be scanned daily because, unlike most public libraries, their arrangement doesn’t follow any standard classification. A volume’s position isn’t fixed or dictated by its subject, publisher, title, or author but instead changes constantly, as users are encouraged to place books back on the shelves freely.

In The Dynamic Library — a series of essays that laid the theoretical foundations and provided background for Sitterwerk’s organization of knowledge — Gerhard Matter writes that in the nineteenth century, books have ‘disappeared,’ becoming mere ‘numbers on a catalog.’ The advent of the internet has facilitated the fragmentation of culture (not necessarily a bad thing), proving how the world we know results from an intricate, ever-expanding network of notions and ideas. Culture thrives chaotically on countless individuals thinking, researching, and creating — rather than following institutional norms and predefined paths. Systematic, orderly classifications — Matter continues in the text — have the unrealistic ambition to be overly comprehensive. But can knowledge ever be considered complete? Instead, libraries should encourage users to ask complex questions and work collaboratively as well as independently. Didn’t Umberto Eco say that libraries should be ‘models and images of our world?’

A staunch opponent of standard classification and enforcer of individual creativity in the library was Sitterwerk’s co-founder, Daniel Rohner, who always refused to arrange books according to conventional models. When they decided to develop the art library, Felix Lehner recounts, Daniel couldn’t help but influence its architecture, too: “He thought having a huge wall of books was a terrible idea. His vision of the library was something else entirely. It would have been a universe in itself — a public library, but one that could truly come alive.”

© Marta Dell’Era

The initial Kunstbibliothek mainly consisted of Rohner’s books — an extensive overview of contemporary art texts, exhibition catalogs, and monographs assembled over 45 years — to which Lehner later added his own. Rohner used to spend days moving books around the shelves, regrouping them for visiting researchers and artists in compilations that followed completely subjective principles. “He would place books next to each other of or about artists that in life had some kind of dispute, as if he tried to make it alright,” a former colleague recalls. Through constant human curation and intervention, new, unexpected worlds and connections emerged. Lehner describes how “Each and every surface of any given room held books — all the shelves were filled, and often, even the floor. I admired his book compilations, which changed every few hours into new combinations.” The librarian’s original approach had a deep, albeit brief, impact on Sitterwerk’s mindset and vision. After Rohner’s passing in 2007, the team couldn’t just confine the books into standard catalogs. To understand contemporary culture, they believed interdisciplinary thinking and collaboration should be implemented into the formula.

The overall space was redesigned in a neat, modernist aesthetic and organized as a laboratory for ‘the library of the future’ to encourage subjective organizations of information and to free objects and books from the constraints of drawers and shelves. The earliest phase in the making of Sitterwerk’s now iconic Dynamic Library was equipping all the books with radio frequency identification (RFID) chips — a technology commonly employed in anti-shoplifting systems. Among the shelves, an RFID reading antenna — the buzzing robotic arm that performs the shelves’ inventory every night — scans the tags and transmits each book’s location to a central database — the library’s digital catalog.

As the Kunstbibliothek advanced, the main table on which people laid their research remained a basic wooden desk — the only timid innovation being a second scanning antenna that extracted lists of the books on top. “What if the table knew what Daniel set on it, and what if that knowledge could somehow be stored?’ Felix Lehner recalls thinking. Planets aligned in 2011, when Sitterwerk and Zurich-based design and development studio Astrom / Zimmer & Wegmüller (now A / Z & Tereszkiewicz) discovered an affinity to each other’s work. “In the mid-aughts, we were interested in how information becomes knowledge — which is the very core of a library, isn’t it?” says co-founder Anthon Astrom. “We were focusing very much on text. While the way we consume text has changed significantly during history, writing hasn’t. You write words with your pen or type a blog post, but the result is always a linear document. At the time, we were building interfaces for writing differently, experimenting with new ways of recording text.”

Rohner used to spend days moving books around the shelves, regrouping them for visiting researchers and artists in compilations that followed completely subjective principles.

Lehner asked Astrom and his partner, Lukas Zimmer, to design a system that would implement the principles of the dynamic order into the library and translate Rhoner’s forma mentis into hardware and software. “We sat down with Sitterwerk’s team, and together with the library’s architect Lukas Furrer and Infomedis, a company specializing in RFID technology, we created the Werkbank,” says Astrom. Its main feature is a research desk dubbed ‘sensory table’ — a physical space to sit and research that borrows its name from carpentry-equipped tables (workbench, in English).

With Furrer’s modernist design, the Sensory table Astrom and Zimmer conceived hasn’t changed since they inaugurated it in 2015. It has a dozen antennas underneath and two cameras on top so that everything laid on the table can be simultaneously scanned from beneath and photographed from above. On the monitor incorporated into the structure, a digital interface generates a real-time overview of the research: not only a list of what’s on the desk but also how books are laid out, their position, context, and even size. “You take your books out, you lay your material in front of you, move it around, read things, write notes — we believe that the process of you laying things on the desk, moving and rearranging them, is part of how you internalize knowledge,” Astrom explained in a 2018 conference in Helsinki.

Research, however, is useless unless it’s shared. What to do with all the knowledge Sitterwerk generates? How to feed it back into the library for everyone to use? The next step for the Kunstbibliothek was creating a system allowing visitors to gather their own bibliography and notes together into research maps in the form of fanzines. As the scanning of what’s on the table is complete, users can rearrange their research on the monitor. “You can move these things around, scale them, rotate them, change the background.” Then, you can drag and drop other books and notes into a page layout, print it, bind it, and put the booklet on the shelves, complete with its own RFID chip. The Bibliozine was born as a tool to navigate and bump into other people’s research: “Thanks to this principle of dynamic organization, you can come across books for which you were never even looking,” Lehner comments.

© Marta Dell’Era

Sitterwerk is primarily a place of production where materials are brought in, changed, combined, created, or destroyed. Since its inception, the Material Archive was introduced as an essential, haptic counterpart to the books. A massive, five-meter-high self-standing metal cabinet opposes the shelves, housing more than 2,5000 samples in its hundreds of drawers.

Wayne Switzer, the section’s manager, explains that most samples come directly from the foundry. “The artists we work with here in the workshops experiment with many different materials: plastics, metals, wax, ceramics…the most interesting become part of the library.” Other additions, like this 3D printed glove or this aluminium-coated polyester fabric, are just for fun.

“This is a place of connections,” Switzer continues. “When people come here to research, they need to establish connections between books and materials. If you’re an artist or an architect, you work this way anyway, right? Understanding comes through interactions — it doesn’t just happen in the mind, but through all the senses.” This is also why visitors are encouraged to explore the materials, touch them, photograph them, and eventually incorporate them into their research using the Werkbank. (Laguna~B has recently donated 12 glass samples exemplifying Murano’s most relevant techniques to Sitterwerk’s Material Archive. For the occasion, our team’s Marta Dell’Era and Erica Toffanin co-curated the exhibition Silicate + Sodium + Calcium, offering glimpses of founder Marie Brandolini’s original research process through an intimate, personal lens. It’s open until July 3, 2025 in the Kunstbibliothek.)

© Marta Dell’Era

Sitterwerk’s unique organization of knowledge illuminates two aspects of the contemporary approach to culture. One is that something got lost in the passage from researching in libraries — where finding sources and verifying information was a slower, more complicated process requiring physical presence and involving sensory experiences — to internet-based research — which is expansive, shockingly faster, and grants access to far more information, but sacrifices the intermediate steps or ‘anchors’ that lead to discovery. Astrom, who spends most of his time working with data transformation, defines the ‘anchor points’ as invisible landmarks, essential passages that help humans internalize and create knowledge. “If things come to you too easily, information doesn't stick.” When you had to search for a book before the internet, for example, you physically had to travel to the library, speak with the librarian, remember the volume’s code, visually scan the shelves, and often navigate the space in a trial-and-error process before finding what you were looking for. Obviously, that’s not the case when you type a question on Google. Part of Astrom Zimmer’s challenge, he says, is trying to introduce anchor points in the digital space as well — “Sometimes we manage, sometimes we don’t.”

Subjectivity (and often humanity) has historically remained outside places of institutionalized culture, such as libraries and archives.

The internet often presents information isolated from its original context — especially in social media, where the content we consume arrives already processed and mangled by algorithms that regulate the platforms. But in reality, nothing exists outside a context, and this atomized approach inevitably impairs real understanding and even the notion of truth. “When you look at a piece of data, a report, or a book, you see it next to other pieces of data…you know where it is and what’s related to it. Adopting a bird-eye perspective, no matter what the structure is, is crucial to recognize where on this big map you are.” In Eco’s Il Nome della Rosa, the two protagonists only uncover the library’s secret after sketching a map that allows them to see it from above.

The second thing Sitterwerk proved is that the researcher’s own knowledge and curatorial potential are rarely recognized as assets that are worth integrating into the system, but they should be. Subjectivity (and often humanity) has historically remained outside places of institutionalized culture, such as libraries and archives. By giving people space and freedom to experiment, share, and discover, Sitterwerk pioneered a new model — turning the intuition of a single (genius) mind into a system where knowledge can thrive and expand. “Without Daniel’s driven yet unsystematic way of getting distracted while arranging and rearranging the books over and over again, we probably wouldn’t have come up with the idea of using dynamic organizing principles,” Lehner comments.

In the world, as in the library, we have the power, the duty perhaps, to curate alternative worlds.

The clock strikes 3 AM, another scanning shift begins. The books have moved again.

Caterina Capelli is a freelance culture writer. Since 2021, she’s also Laguna~B’s communication manager and editor.

Daniel Rohner, book collector and Sitterwerk’s co-founder, who inspired the library’s Dynamic Order. (Courtesy of Katalin Deér)

Caterina Capelli is a freelance culture writer. Since 2021, she’s also Laguna~B’s communication manager and editor.