An Archive for the Sun and other Stars

Glass lenses, a film with Mastroianni, and traces of Steve McQueen's charisma: Delving into Persol’s archives.

Cellulose and glass, glare and dust

This story begins in Turin, by the River Dora. It was 1917: the engineer, photographer, and pilot Giuseppe Ratti purchased an optician's shop to start producing avant-garde sunglasses, with lenses designed to protect the eyes from the sun’s glare and the dusty roads of the time. The brand’s name, Persol, is a contraction of the Italian ‘per il sole,‘ meaning “for the sun.” The frames had experimental shapes and were created from bars of cellulose acetate, a plastic material that generated unique patterns on each pair of glasses. As World War II ended, and Turin's population rapidly doubled, the building next to the Dora River became too small. Legend has it that, looking for a new location, Giuseppe Ratti followed the Dora River to the point where it flowed into the Po River, continued along Corso Casale, and arrived in Lauriano, a small village east of the city. There, he found the perfect space for Persol's expansion. It was 1955. From then on, every pair of glasses Persol sold — with their signature acetate frames and exclusively glass lenses — was produced inside that factory on the outskirts of Turin.

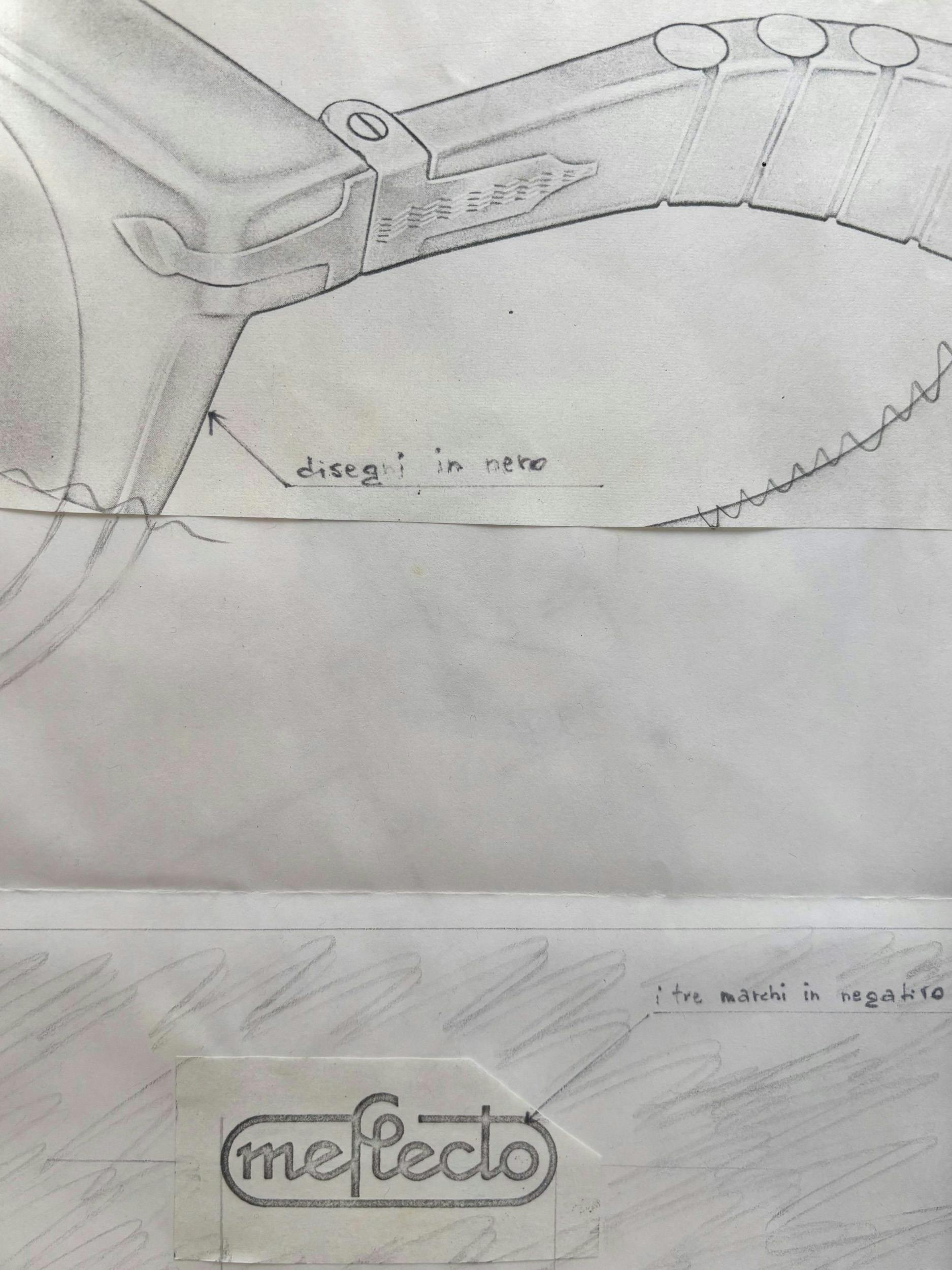

The unmistakable arrow and the Meflecto cylinder system. Beyond aesthetics, these two elements also contribute to the perfect fit. (Photo: Giacomo Golinelli)

Something familiar

As I arrive in Lauriano, driving along Corso Casale 70 years after Ratti, Luciana Crovella welcomes me at the gate. Everyone at Persol knows her; she’s worked there since the 70s, starting when she was just 18. She has clear blue eyes and introduces me to my guide, Gabriele. He’ll take me through the production department. He is younger than me — probably in his 30s — and has clear blue eyes, too. For someone with such light irises, I realize sunglasses are essential. To Gabriele, sunglasses are also a passion he’s eager to express. His job consists of coordinating the advancements of new products. As we wander around together, he describes the numerous stages required to create a pair of glasses. It’s twice as much compared to average sunglasses. The people we meet in the factory approach him lovingly, almost like an old friend. A sense of family fills the air at Persol.

Gabriele explains that the iconic arrow-shaped detail isn’t just for aesthetic purposes. It’s functional, too, because it makes Persol’s hinges more resistant. The steel arrow embedded in the acetate frame is familiar to me: My father had worn Persol sunglasses for years. They were manufactured using the same process I’m witnessing now: It’s fascinating to see how an acetate bar is turned into a pair of glasses.

Something in this place will always be familiar to every cinema-lover, too, as it was here, at the beginning of the 1960s, that someone assembled the glasses that Marcello Mastroianni wore in the Oscar-winning film Divorzio all'italiana. Almost ten years later, someone created the pair that Steve McQueen wore on the set of The Thomas Crown Affair. Everything started right here.

An artisan works on the finishing of a pair of Persol glasses at the historic Lauriano plant in Turin. (Courtesy Persol)

A story that is a trajectory

This story is a trajectory through space, connecting Persol to Barberini (the world leader in the optical glass lenses market), Northern to Central Italy, and the Po River to the Adriatic Sea. In Barberini, I meet Francesco De Luca, one of the company’s artisans. His father, too, had worked in Barberini: he remembers him at his work table, perfecting the lenses for the model 649 worn by Mastroianni — nothing short of a style icon. De Luca’s family has been committed to producing the finest optical glass on the market for decades. Making lenses is a trade based on passion, handed down through generations. In Barberini, skills are specific, and many variables exist. To achieve geometric perfection and correct refraction, rare earths are mixed with silicon and metal oxides, resulting in a transparent material that offers a better definition than the naked eye.

As I listen to De Luca explaining the main glass processing phases, one detail particularly fascinates me: Optimal transparency is not the result of a linear process. When the glass initially comes out of the furnace, it’s rough but round and already transparent. It’s then smoothed and curved, with an angle calculated to the micron, but turns opaque. It’s pleasant and soft to the fingertips, nicer than finished glass, but you can’t see through. The lens gets its transparency back only in the final steps. Eventually, it’s ready to be mounted on the frame. De Luca explains how the risk of breaking increases with every passage: as the process unfolds, the glass becomes thinner and thinner. “Sometimes it breaks and we have to start again,” he tells me. Yet, that’s all part of the path towards perfection.

When asked how long he’s been working here, he replies: “I began at 7.30 AM on August 23, 2004.” Precision is a talent. “Did you arrive with your father that day?” I continue. “No, we came in two different cars.” The sense of family here goes hand-in-hand with loads of professional pride.

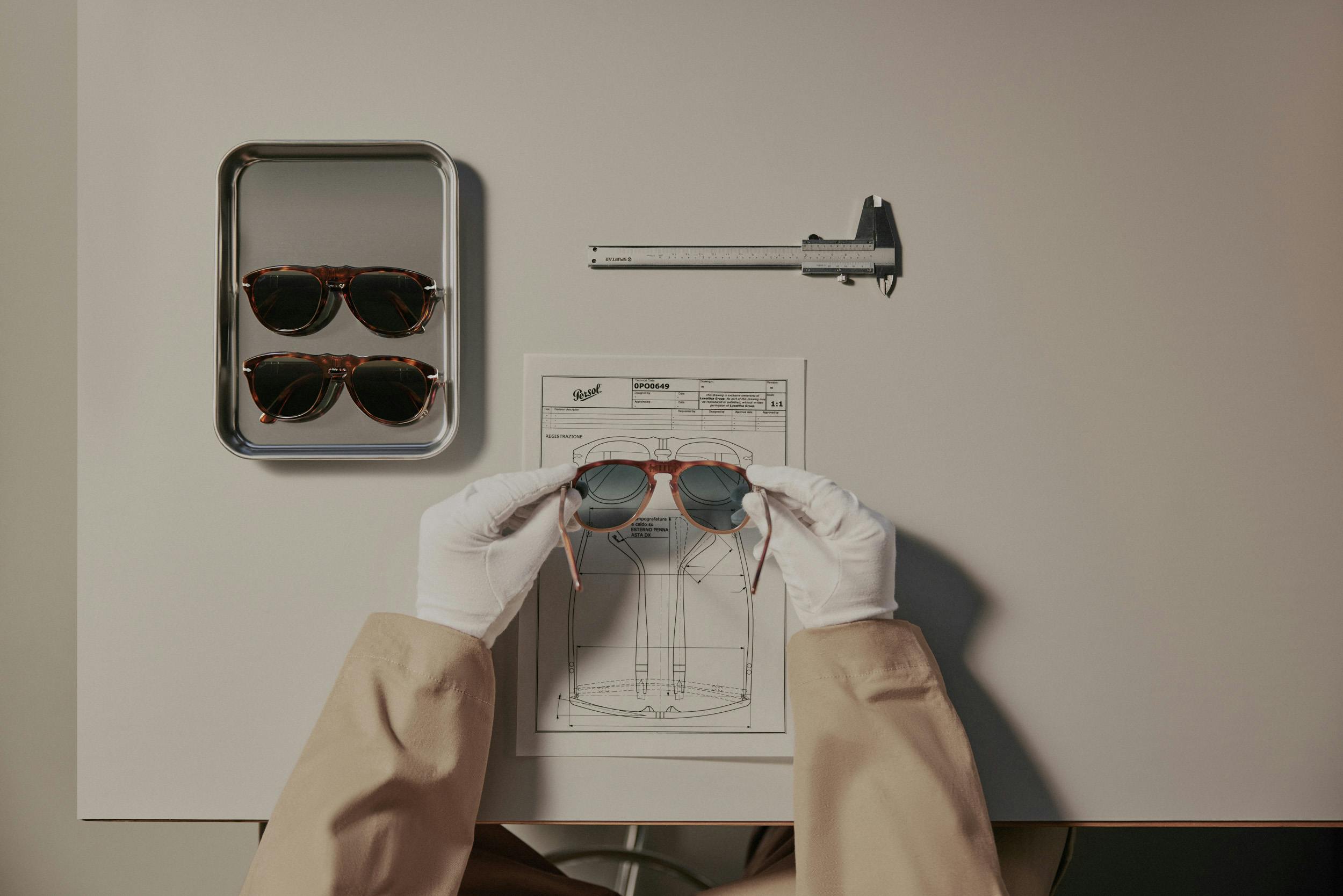

The registration phase, where it is checked that the assembly has been done correctly and that the glasses have no deformations. (Courtesy Persol)

A glass and acetate sculpture

Both glass and acetate are transformed and curved through heat. However, an optical glass lens and an acetate frame also share a process that makes them special: subtraction. The raw glass that arrives in Barberini is chiseled, polished, and expertly levigated to its final shape until it becomes, from every point of view, a perfect lens.

On the opposite side of our trajectory, at Persol’s headquarters, acetate arrives as rectangular bars, a few millimeters thick and over a meter long. Except in a few cases, the texture is inevitably varied: The process is natural and the result can only be partially controlled. Each area of the bar is unique, and no two patterns are alike. Every piece is carefully hand-chiseled, ground, and shaped to craft the frames.

It’s not like injecting a substance into a mold. It’s a skillful subtraction process. You need imagination and vision to conceive it. At both ends of our trajectory, perhaps unknowingly, Francesco De Luca and Gabriele Brusa describe the same process. As I listen to them, I get distracted and end up thinking of a ‘sculpture’ emerging from another material; I think of the process that ‘liberates’ a work from an irregular shape. My mind conjures up the image of the corridor of the Accademia in Florence, where Michelangelo narrates the poetry of his Prisoners, freed from the marble.

How the front of a pair of glasses is created — by "subtraction" — from an acetate sheet. (Courtesy Persol)

Like Steve McQueen

Every story, just like every trajectory, crosses time. At the end of the day, I find myself sitting and talking with Riccardo Pozzoli, Persol’s creative director. Items from the archive are spread on the table and behind him on the wall: Photos of movie stars, advertisements from various eras, sketches, patent documents, and, obviously, lenses, both old and new. A black frame with a test sticker and the handwritten word ‘approved’ is dated November 5, 1975. Testing was, and is, a manual operation that hasn’t changed in time (I had witnessed it just a few hours before.) A series of metal pins and joints are visible between the lenses, allowing the glasses to be folded into a pocket-size case. I ask Pozzoli what his first memory of Persol is. He says he recently found a photo of his 20-year-old self sitting on a bench, bathed in sunlight. He’s wearing the 714, McQueen’s model, the one with the folding metal system between the lenses. “I had the helmet, too, and as soon as I could, I even bought the same motorbike as Steve McQueen.” Even for Pozzoli Persol means family history — a thread emerging from many personal archives. With him, we talk about how Persol has been remarkably preserved in time despite everything it has withstood. For those who love glasses, this small but prestigious company in the outskirts of Turin is a holy grail, an inviolable treasure. The trajectory now appears like a curve in time, just like that of a lens. Similarly, it should help us see what lies ahead as clearly as possible. In their archive, I find records that might help us draw the next little trait of this trajectory. To Pozzoli, holding the black 714 frame with the metal joint, its pinnacle is the creativity in its engineering. Functionality becomes design and, ultimately, style, expressed through these harmonious, pocket-size, precious sculptures made of glass and acetate.

ARCHIVIO is Promemoria Group's editorial project. It promotes the use of archives to design a better future, experimenting with new curatorships. A magazine of unpublished and exclusive stories, distributed from New York to Hong Kong, from the MET to the Centre Pompidou.

The production phases of a lens, from the semi-finished piece to the treated lens. (Courtesy Persol)

ARCHIVIO is Promemoria Group's editorial project. It promotes the use of archives to design a better future, experimenting with new curatorships. A magazine of unpublished and exclusive stories, distributed from New York to Hong Kong, from the MET to the Centre Pompidou.