Sustaining the Sparkle

Radical Jewelry Makeover champions glitz without guilt, one transformed treasure at a time.

Once upon my childhood, wandering through a chic shop hand-in-hand with my grandmama, I found wonder in an unlikely object: A tiny keepsake box made from the intact, dried rind of an orange. I marveled over the texture of the skin, the delicate lingering smell of the fruit, the way the lid fit perfectly onto the vessel. I begged to take the box home, but grandmama, whose love for luxury was always tempered by the practicality of her strict Peruvian Catholic boarding school upbringing, dismissed it as trash and moved us along.

The transformation of trash into treasure was, perhaps, the thing that fascinated my young brain most about the box, and nearly four decades later, I know I’m not alone. As the world resonates with the buzzword of creative reuse, Radical Jewelry Makeover (RJM) has pushed the idea of upcycled materials into the mainstream of the art jewelry community. RJM is a programmatic wing of Ethical Metalsmiths, an international alliance dedicated to bringing about “a jewelry industry where a beautiful product does not bear a human or environmental toll.” Through advocacy and education, organizations like Ethical Metalsmiths, the No Dirty Gold campaign, and the Artisanal Gold Council aim to reduce the staggering human and environmental tolls of procuring new jewelry materials.

In Jewelry is Political, metalsmith and educator Elizabeth Shaw describes these initiatives as disruptive and political tools, “drawing attention to practices that are usually hidden.” One of the most sobering statistics shared by No Dirty Gold shows that the mining necessary to produce one standard gold wedding band generates 20 tons of rock waste. It takes a pretty callous consumer to be indifferent to that calculation, and collectors are increasingly seeking out what Kathleen Kennedy, co-director of RJM, calls “farm to table jewelry.” Reminiscent of Alice Waters’ ethical food revolution, socially conscious buyers now ask where and how the components of their adornments were mined.

RJM donations, pre-sorting. Costume jewelry, heirlooms and oddities piled together and awaiting transformation. (Courtesy Emily Culver for RJM)

Bypassing the need to unearth new materials, RJM identifies as a “community mining” project. Twenty iterations have now spanned the globe from Richmond, Virginia, to Brisbane, Australia, led by Kennedy and Susie Ganch, who began the project in 2007 with artist and sustainable jewelry consultant Christina Miller. Before each event, RJM launches a call for donations from the area for unworn, outdated, or broken jewelry, amassing raw materials for jewelers and jewelry students to give forgotten trinkets new life. “People donating their unwanted things allows them to become emotionally invested in what's happening. And then they become part of the solution,” says Curtis Arima, who chairs the metals department at the California College for the Arts in San Francisco and has been working closely with RJM since it revolutionized his practice in 2008.

The donations are sorted during a lively volunteer-powered event, which gives the organizers the opportunity to share information about the impacts of the jewelry industry to the larger community. Anna Akers, the founder of Lorak Jewelry, participated in the Fall 2024 RJM. Near the end of the sorting session, she lucked upon the “find of the day” in the bin of materials discarded as not-quite-worthy of RJM transformation: a pair of gold-and-amethyst earrings whose funky design suggested an origin in the 1980s. Akers is particularly sought after by her clients for her ability to take outdated family heirlooms and refresh them through a contemporary lens, so it is no surprise that her trained eye spotted these valuable raw materials just waiting for their makeover moment.

Students at the Norfolk, Virginia RJM in Fall 2024 beginning the sorting process. (Courtesy Emily Culver for RJM)

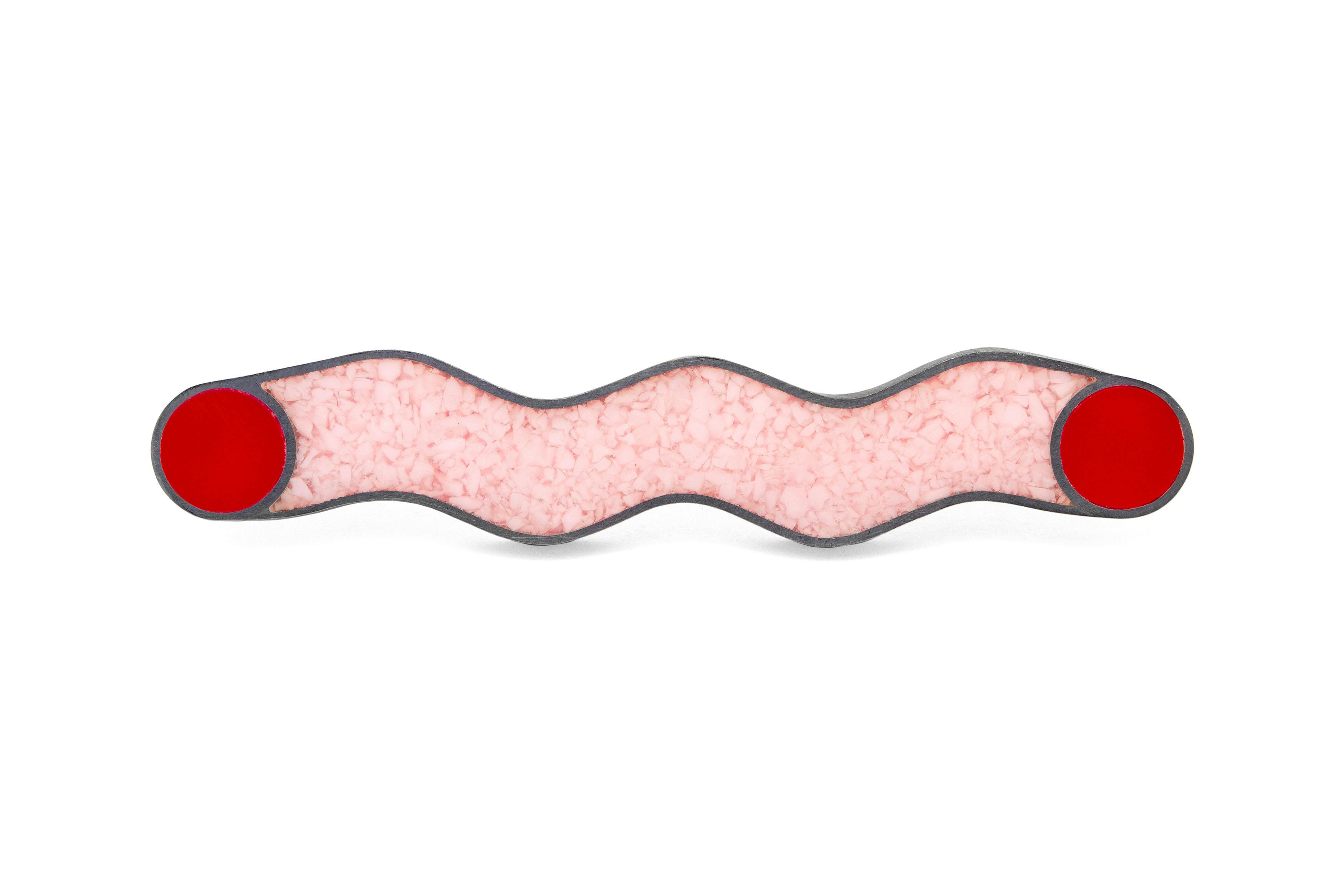

Part of the fun of RJM is seeing how the most outlandish, even garish, jewelry components can be reimagined into thoughtful and elegant designs, like Erica Bello’s squiggle brooches made from discarded mardi gras beads. Even so, precious metals like the gold Akers spotted are still hot commodities in the sorting room. Akers notes that RJM’s approach is new, but recycling of precious metals certainly is not — they’re “always being reused. There’s no way to know that there's not ancient Roman gold in our jewelry today, because if it's recycled, it's been recycled over and over and over again, which is really cool. What other material gets reused like that?”

Manipulating these materials takes a skilled touch and years of practice to get right. RJM’s outreach connects emerging jewelers with mentors, building new legacies of craftsmanship by teaching what Ganch calls “wiser practices” for their future studios. These include preserving every snippet of scrap and speck of metal dust for reuse, as well as training in how to safely reconstitute those remains into ingots, from which they can start fresh components without buying new materials. Curtis Arima credits RJM for turning on a “light bulb for me and for several of my students. I love the way it brought the metalsmithing community together, about making, but also questioning the way we make, diving deeper into things we hadn't considered, like the way that it really impacts communities, the earth, health, and social justice. And how we, as individuals, can really make a difference.” Arima’s studio manager, Russ Larman, was one of Arima’s students when he participated in the 2008 San Francisco RJM. Now, thanks to their advocacy and interventions, CCA’s jewelry department has eliminated harmful and wasteful processes in pursuit of the most sustainable jewelry practice possible, documenting their journey so that other studio managers can achieve the same results.

“If we’ve been wearing jewelry for 65,000 years at least, communicating with adornment isn’t going away. It’s intrinsically in our fiber.”

To Arima, sustainability means more than just environmental safeguards; he measures progress against the United Nations Foundation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Among these, gender equality, zero hunger, no poverty, decent work, and economic growth are key to understanding that sustainability needs to be approached holistically. Arima handily demonstrated this sensibility when he transitioned the CCA studio to using boosters and compressors, which replace the need for bottled gases by optimizing publicly-supplied natural gas or ambient air. This cuts down on the demand for gas overall, eliminates the carbon footprint of transporting the bottles, is safer from a hazardous materials standpoint, and ultimately saves the department money. Emerging jewelers whose first studio exposure includes this technology are vastly more likely to rely on it in the future, amplifying the environmental benefit and helping them create a financially stable practice at the same time. Affordable methods can broaden access to a craft career for historically underserved communities, a consideration of vital importance for Arima and Larman, who deliver joint lectures on the intersection of sustainability and diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives in the craft field. They consider RJM an ideal teaching tool to deliver, as Arima puts it, a “thought provoking journey around sustainability that you can feel in your heart as well as intellectualize.”

Curtis Arima’s works range from exquisitely balanced clusters of filigree to jeweled encrustations like these, but since working with RJM, his focus has been steadfast on sustainability. (Courtesy Curtis Arima)

Emily Culver, an artist and educator who worked with Ganch and Kennedy at Virginia Commonwealth University and helmed the Fall 2024 RJM in Norfolk, Virginia, saw this same magic affect her own students. One of her undergraduates was so moved by the No Dirty Gold statistic about the 20 tons of rubble created per ring, they created a new research-based body of work in response. The jewelry line’s beaded necklace has a weight proportionate to the waste created to mine the gold for one jump ring. (Unfamiliar with a jump ring? Visualize the single, delicate loop to which the clasp of a lightweight chain attaches.) Culver’s own body of work is highly technical, minimalist and conceptual, and therefore not always compatible with recycled materials. She admits she often has had to sacrifice sustainability in service of her concepts, but credits RJM with inspiring both her and her students to think about how to put things together in a way that allows for easy reuse or recycling. “For us, maybe that was even the most impactful lesson, because a lot of them will probably continue making work in metal, which has its inherent waste. But if you're thinking about how you put something together so it can come apart again, that's a new approach.”

“There’s no way to know that there’s not ancient Roman gold in our jewelry today, because if it's recycled, it’s been recycled over and over and over again.”

According to Elizabeth Shaw, RJM’s two Australian editions in 2010 and 2016 have had a significant, long-lasting impact on their local communities. The national broadcast picked up on the story of an international jewelry project coming to Queensland, and the resulting flood of donations came in from all across the country. For Shaw’s students and peers, working with the donated materials was transformative on many levels. Before RJM, Shaw says her contemporary jewelry students might have been “inclined to go and buy some glitzy piece of jewelry to wear out for one night.” Being confronted in the sorting room with discarded fashion jewelry pieces indistinguishable from the contents of their own junk jewelry drawer brought the abstract ethics of what one wears into reality at their fingertips.

The whole experience was a catalyst, says Shaw. “A lot of jewelers were doing things that were sustainable in their practice, but doing it collectively in that environment is a very empowering process. It made the participants much more open to sharing ideas. Sometimes jewelers, when they work on their own, can be a little insular in terms of what they’ll discuss or share… But everyone who participated has continued to keep in contact and share information.”

Eight years after the last RJM call went out, Shaw still receives packages from people hoping to find new life for their old bling, as well as inquiries from buyers eager to support the project by collecting the madeover pieces. Because of the ongoing donations, Shaw runs RJM-style workshops with her students on a regular basis, and mounts reuse-themed exhibitions where those eager buyers can snap up works that speak to their conscious consumerism.

“Jewelry is meant to speak for us,” Katherine Kennedy says. “We wear things so that they can say things, and wearing a piece of RJM jewelry is saying a lot. It's allowing you to get political, to share your values.” Ganch agrees. “If we've been wearing jewelry for 65,000 years at least, communicating with adornment isn't going away. It's intrinsically in our fiber.”

Education is central to the RJM mission. Student Theodore Mayberry from Emily Culver’s RJM class submitted sketches of their work in progress, documenting the transition from donation to exhibition-ready work. (Courtesy Emily Culver)

We are connected to the objects we wear so close to our bodies — earrings that tickle our neck throughout the day, the bangles that announce our movement, the heirloom necklace that embodies a precious memory while accentuating the natural sparkle in the wearer’s eyes. No surprise, then, that there have been eerie moments of connection between the donors and the final works. Shaw recalls artist Bibi Locke’s madeover necklace, for which she had scavenged through sorted, deconstructed donation elements to create a singular piece. “From the thousands of items she could have chosen,” Shaw says, “the necklace contained parts from the donations of three dear friends.” At an exhibition opening for one of Shaw’s long ago reuse-themed exhibitions, Deborah, a colleague of Shaw’s, had just purchased a pair of madeover earrings. While gushing over her purchase to Shaw and the earrings’ artist, she offhandedly remarked, “It doesn’t look like anyone used that hideous, huge copper cuff that I donated!” Shaw and the earring maker held back laughter while enlightening Deborah. That “hideous cuff” had been transformed into her favorite new earrings.

“Making has the power to transform lives, communities, and futures. This series will explore the impact of maker communities from around the world, from a diverse array of media and methods. As we face the modern challenges of climate change, authoritarianism, and inequality, how are the world’s artists and designers putting their wealth of creative problem-solving skills to work? What responsibility do we have as makers to craft a better world, and what responsibility does the rest of the world have to support our artists and creatives?”

— Jennifer Hand

Mardi Gras beads are unrecognizable in this mod RJM brooch by Erica Bello. (Courtesy RJM)

“Making has the power to transform lives, communities, and futures. This series will explore the impact of maker communities from around the world, from a diverse array of media and methods. As we face the modern challenges of climate change, authoritarianism, and inequality, how are the world’s artists and designers putting their wealth of creative problem-solving skills to work? What responsibility do we have as makers to craft a better world, and what responsibility does the rest of the world have to support our artists and creatives?”

— Jennifer Hand