Memoria

A short story by Maria Luce Cacciaguerra

It’s all about asking the right question to the water.

“Queste cose non avvennero mai, ma sono sempre” — Sallustio, Degli dei e del mondo.

In the beginning, there was no word. There was no light. In the beginning, there was water. Before time, before almanacs, there was a brackish vastness where, before they were charted or claimed, waters spoke to each other in languages that humankind, soon to arrive, would never understand. A place — or perhaps a non-place. The universe was not silent, but waiting. And the waiting knew. The waiting remembered. There, in that dark, cosmic womb, something was dreaming. Not a god. Not a man. Something older.

A thought without a body. A shadow longing for the weight of ground beneath it.

The dream was pretty simple: a threshold. A place to stand between what flows and what remains.

Out of the dream came the barene.

Not islands. Not land. Not sea. But shifting, muddy patches of salt and silence that appear and vanish with the sea’s breath. Places where impermanence reveals itself. The barene are not space. They are visible time.

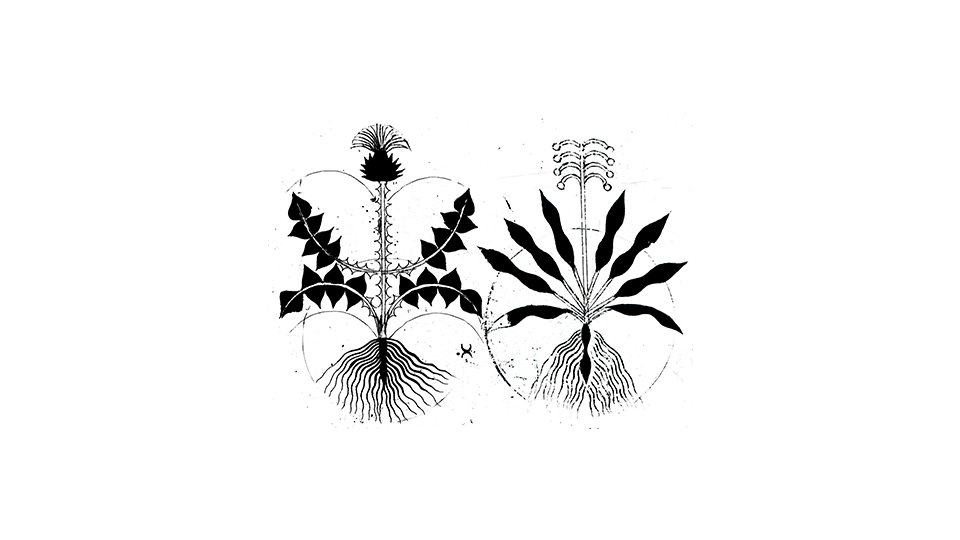

The first plants did not come by wind, but by waves. The sea carried them: seeds thick with memory — saltwort, salicornia, succulent chamaephytes. Each plant who took root was a memory trying to anchor itself. Birds nested. Fish circled, or stranded, as if waiting for a revelation.

Long afterward, when things began to have names, some wanderers decided to stop — then vanished without a trace, as if the sandbar had absorbed them into its own body. It absorbed their memories.

The sea, who forgets everything, never forgot the barene.

The barene did not forget the wanderers.

One moonless night, a barena rose. She became ivy. For six days she clung to nothingness. And then she vanished. Some say it was an experiment by the gods. Others say it was a barena who dared to defy memory. Since then, every barena born is an attempt to remember the one who vanished. Time, tired of going forward, tries — in every little piece of land — to go back, to stay still.

But the wanderers returned, this time to stay. They invented names. They invented maps. They drew lines. Built dams. Diverted rivers. They traced endings onto beginnings. They believed they could stop the flow with ink. They convinced themselves they could stop the flow with drawings.

And so the barene began to melt. Not out of anger. Out of sorrow. Like forgotten ideas. Like stories never told. It is the fate of things.

But barene do not forget. They remember everything. They remember steps that left no footprints. They remember those who passed and those who never returned. They remember whispered words, names that no one dares speak anymore.

Every barena is an archive of the possible.

From this breath of memory and absence, Venice was born. Not a city. A question.

A body suspended in history, built on a grammar of water and time.

A sleeping fish swimming through the dreams of those who sleep beside its canals. Its bridges do not connect places, but concepts. Its calli do not lead to destinations, but to questions.

Venice walks. Venice remembers. Venice breathes. And every night, when the thick fog comes, and reality withdraws to make space for the symbolic, the barene sing.

Not with voice, but with being. And those who listen understand — or dream of understanding — that one must always ask the right question to the water.

Because the water knows.

And the water, like Borges, tries never to forget. Always.

When from the sea to the sea the land returns — clumsy, invaded by the now putrid waters of the canals — I imagine the slow descent into the abyss of those who believed naming things would be a solution.

At last, everything returns to water.

In an uncanny spectacle, we see the moon, spiders, plants, lightning — all in conversation: a limonium with a beautiful trunk, snails and ants, dried flowers, artichokes, a black horse, a white horse, mules, crabs — all dying together, carried away by the water.

“There is nothing strange. It has happened. It will happen again.”

Only the plants that share their lives between land and lagoon survive.

Amaranthaceae, Salicornia fruticosa, the water-storing succulents.

Erect, fleshy bodies with tiny scalelike leaves — red with memory, paired and opposite, pressed against their stems like forgotten scales.

Their flowers, nearly invisible, do not seek to be seen.

And when one falls into the water, it leaves a hole in the plant’s soft flesh — like a forgotten story.

The barena whispers to us:

“Because you count me as an empty continent, a wasteland yet to be conquered,

Know that I am worlds, heaths, and broken visions.

I have everything to unlearn.

But because you consider me already world,

When I am still trying to find myself,

I will return to the water.

I cannot return.”

Remember, it’s all about asking the right question to the water.