The Stain

A short story by Thea Hawlin

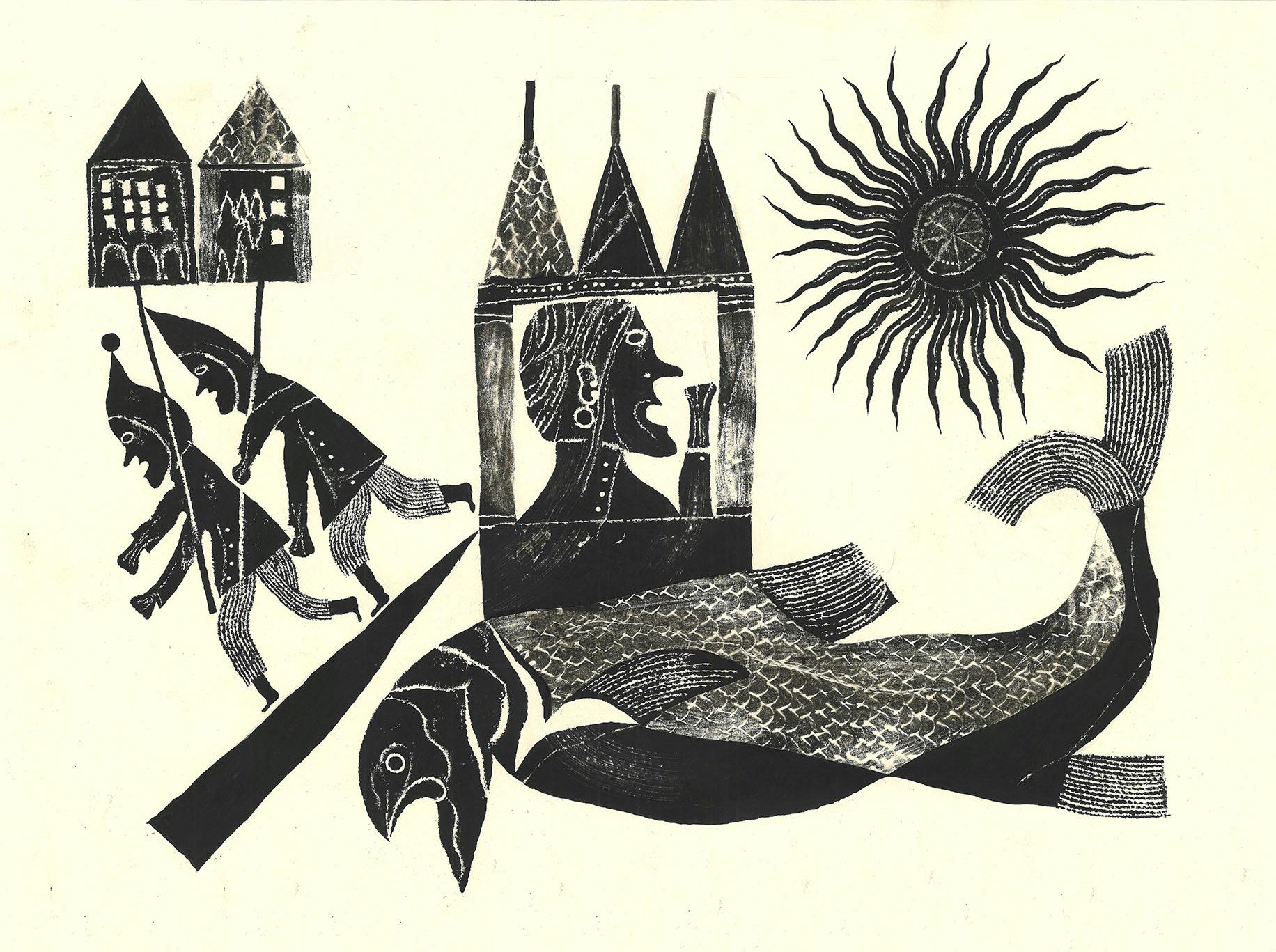

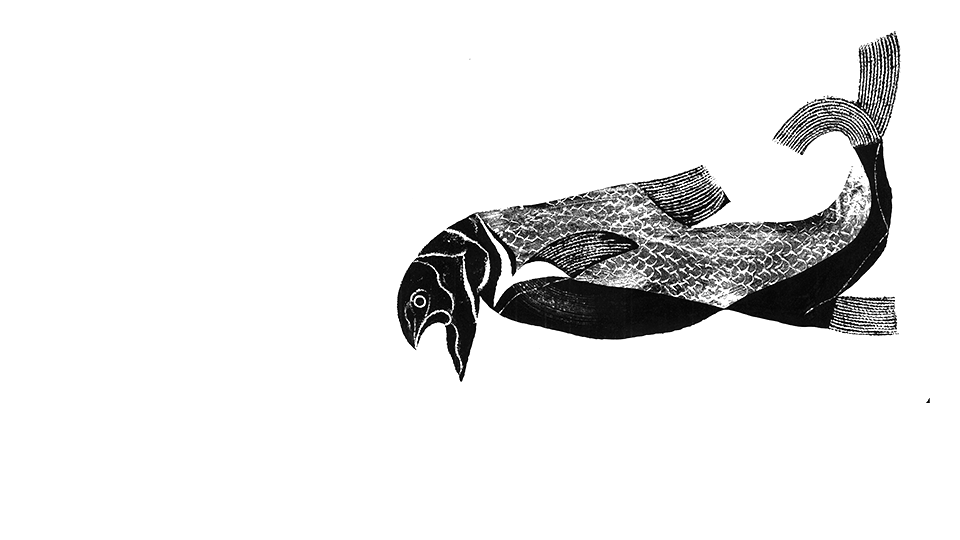

The colour lingers in the water; at first the red slips invisible under the surface, clinging to the bottom of boats, the vaporetti, the bellies of little fish darting around in the shade.

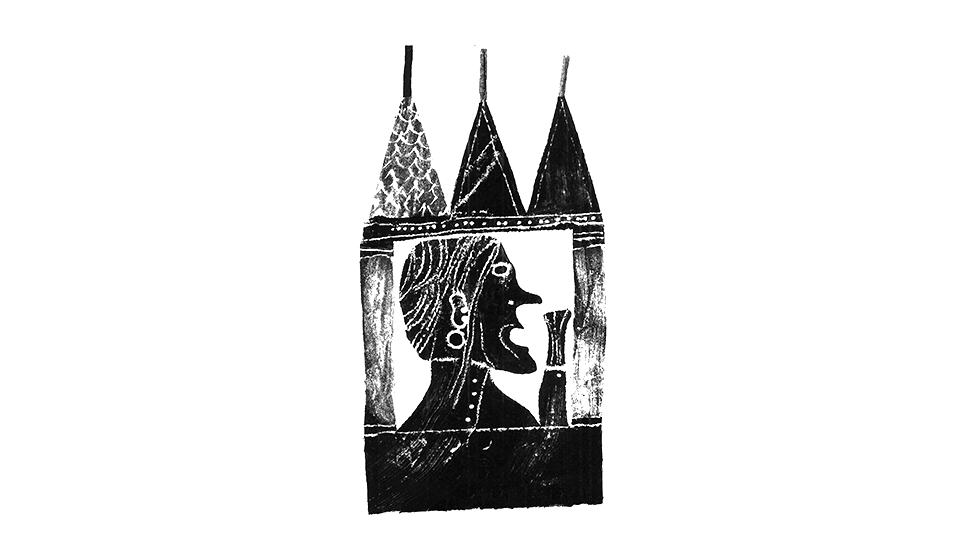

A soft shadow seeps into the city, perhaps a trick of the light, the sunset reaching out across the water, the clouds colouring the canals. The colour grows steadily over time, softly, the gradient creeping up at night until the morning when the city wakes to a deep ruby red. At first, as they open their shutters, the locals sigh. Climate activists. They’ve done this before. Do you remember they once dyed the Grand Canal green? It’s only when they head to work that they realise the colour does not stop; it reaches out across the lagoon. As the morning passed you could see it, the waves softly urging the colour further inland, each motion inking it out further like blood.

Some head to church, sign the stations of the cross. The end is coming. We must prepare. Camera crews descend. Venice is bleeding. La Serenissima no more. A soft creeping feeling. The residents begin to close their windows, sandbags gather around doorways. A sense of foreboding descends, working its way into the fabric of the calle. Venice curls in on itself. Red infects conversation. All anyone can talk about is the colour: when it arrived, who had seen it, how it had grown, what it meant, what it was doing, what it would become.

People say it is a plague, a sign from God, a warning we’ve gone too far. Will the fish die? The fishermen grow afraid of the water; some stop going out into the lagoon altogether. Others swear and dive into it to swim. They wade through the shallow waters to collect clams, soft fleshy crabs, and fish from their traps as they have always done. Defiant. Nothing has changed. Fools. It’s water; what are you afraid of? The fish hold no stain, no colour, and yet people stop eating. The Rialto market becomes a morgue: a silent shrine to the time before the colour came.

Rumours of a toxic waste spill, a cargo ship crashing, a secret lab in Marghera. Scientists take vials of water for tests. Laboratories from around the world call in samples, each have their own theories. Marshland and wetland experts all chime in on major news channels, but no one’s certain.

What if the water infected the local population? What would happen if you touched it? Drank it? A curfew is introduced by the government, fears about people falling into the water at night, a ban on boats altogether. From the Lido you can see it, the soft belt of colour that rides down the lagoon both stagnant and swirling, while the sea remains wild and blue. People talk about oil, the way the colour is the same, as if it is riding the waves, silent and sticky, reluctant to move.

Without humans, the water becomes crowded. Small shoals at first, larger ones follow, the canals become thick with them. Nature, unchecked, thrives. A shift occurs; unmoored and untethered, the waves breaking over and under and through. The people — though landlocked — are still shifting, moving, surging, a force unreckoned and unexplainable rising through them. Friendships begin to strain under the pressure.

Some people begin to talk about creatures emerging from the water, the colour spreading to the land. Fights break out between neighbours. A young man almost drowns. Another man’s wife flees the hospital with their newborn child when she sees the body entering the ward. She leaves drops of blood on the marble steps and all the way home. She cries into the night, her husband’s body curled around her. We can’t stay here.

In the morning as they sleep, the father takes his boat out. He knows the regulations forbid it, but he needs air, space. He pushes the throttle up to high and drives out to the furthest corner of the lagoon. He can feel the water surging under him but he casts his fear aside, letting the uncomfortable knot sit quietly in his stomach as he watches the ripples of white foam against the red. He thinks how strange it is that there has been so much pain from this simple change. How the spectrum of colour in which they all live has altered their lives so radically.

He looks to the sky and craves the soft blue he finds there. How much longer will it last, he wonders. Perhaps this is simply a new reality. Perhaps they will have to move away.

The sun slips over the horizon and the sky begins to transform, the blue of day dissolving, the red of the water creeping into the heavens, as if the colour cannot help but not be contained, as if it now has to stamp itself upon the sky, not a reflection but a refraction, a desire for something more. It’s only then he notices it. There’s an area of wetland where the colour is deep and rich, clustered around a number of forked stems, bright little Posidon’s tritons but thick with bulbous little beads.

He steers closer, bending his neck, and there it is: the source. A smile stains his face.

When he returns home he takes his wife’s hand and kisses it, pressing the soft stem of the plant gently into her palm, the damp leaves a soft impression in her skin, a sliver of red.

Salicorne.

Samphire.